7:40 AM – Moratinos: sunrise from our room.

We ate breakfast at Bar-Hostal Camino Real: toast and marmalade; coffee/orange juice; 2 large bottles of water (12.90€). We departed at 9 am.

We soon crossed the border from Palencia into the province of León.

The province of León was the largest, wealthiest, and most populous province we would pass through on the Camino.

In 856, the city of León, just then repopulated after the Moorish invasion, was joined with the Kingdom of Asturias. The Kingdom of León was founded in 910, when the Christian princes of Asturias shifted their main seat from Oviedo to the city of León. The eastern, inland part of the kingdom was joined dynastically to the Kingdom of Castile first in 1037-1065, again in 1077-1109, 1126-1157, and 1230-1296, and from 1301 onward. Despite these dynastic unions, León retained the status of a kingdom until 1833, when the new Spanish administrative organization of regions and provinces replaced former kingdoms. In 1833, the Kingdom of León was considered one of the Spanish regions and was divided into the provinces of León, Zamora, and Salamanca. The province of León, consisting of the northern part of the former Kingdom of León, is now the northwestern part of the autonomous community of Castilla y León, which was established in 1983.

This province offered the most varied terrain on the Camino. We started off with a continuation of the Tierra de Campos with its flat and well-irrigated agricultural land, with adobe walls of villages. Then we would enter the busy capital of León itself, where almost a quarter of the province’s population lives. León is famous for its pork products—cured hams, chorizos, and morcilla—and the local cheese and quince jelly (queso con membrillo). Then, starting at Astorga, we would enter the Maragatería, home of the Maragato people with their unique culture and cuisine.

10:10 AM – Palencia-León Border: Highway signs for entering León province (Sahagún in distance).

10:11 AM – Palencia-León Border: stone marker for leaving Palencia “El Camino de Santiago Supago por Palencia” [The Camino de Santiago by Way of Palencia] with painted yellow arrow.

We arrived at Ermita de la Virgen del Puente around 10:45.

The Ermita de la Virgen del Puente (hermitage of Our Lady of the Bridge) on the río Valderaduey had originally been a pilgrim hospice, and the path into Sahagún is known as the Camino Francés de la Virgen. The 12th-century sanctuary has Romanesque foundations, but the original pilgrim hospice has long gone. The Mudéjar-style brick chapel adjoins the river in a shady poplar grove. Its highlight is the powerful polygonal apse, where the Mudéjar is inspired more by the Gothic than the Romanesque. The small Roman bridge has two arches.

10:49 AM – Virgen del Puente: MT at Roman bridge over Río Valderaduey.

10:50 AM – Virgen del Puente: MT on bridge.

10:50 AM – Virgen del Puente: view across bridge (with yellow arrow on right) to Ermita.

10:51 AM – Virgen del Puente: Don on bridge.

10:56 AM – Virgen del Puente: Ermita de la Virgen del Puente apse (from bridge).

10:56 AM – Virgen del Puente: sign about restoration of hermitage.

We had already walked 7 km, but Don was still having a hard time with stomach problems. Don rested outside while MT went into the hermitage to check for a baño, especially for Don. The lady inside gave her sellos for both of us. When MT asked about a baño, the lady said there was none. A few minutes later, she came outside to suggest that she could call a taxi for us. We had planned to make a stop 3 km later in Sahagún (pop 170,000), since we had not seen much of the city last year due to rain. We had also looked forward to doing the first section of the Vía Romana (aka Via Trajana) between Sahagún and Calzadilla de los Hermanillos, but realized that route (particularly after Calzada de Coto) would be in remote bush country with little shade or water and no towns—and no bathrooms. So the lady called a taxi to take us the last 17 km to Calzadlla de los Hermanillos, where we had reservations for the night. While we waited for the taxi, we had time to investigate the nearby gateway.

11:05 AM – Virgen del Puente: gateway marking halfway point on Camino (view toward Sahagún).

The town of Sahagún is geographic center of the Camino, since it is the same distance from Roncesvalles as from Santiago de Compostela. The gateway has two statues that are 2.2 m high and reach 3.7 m on pedestals with legends and shields.

11:06 AM – Virgen del Puente: Don at gateway.

11:05 AM – Virgen del Puente: left side of gate: “Sahagún Centro Geográfico del Camino” [Sahagún Geographic Center of the Camino] and statue of Bernardo de Sedirac.

11:06 AM – Virgen del Puente: close-up of sign “Sahagún Centro Geográfico del Camino” [Sahagún Geographic Center of the Camino].

11:06 AM – Virgen del Puente: statue of Bernardo de Sedirac on left side, holding book with “Ora et Labora” (pray and work), motto of the Benedictine Order.

11:06 AM – Virgen del Puente: far side of left statue and sign “Bernardo de Sedirac 10[50?] – 1128 Abad de Sahagún, Arzobispo de Toledo, Gran Impulsor del Monasterio Facundino, Confundador de la Villa” [Bernardo de Sedirac 10[50?] – 1128 Abbot of Sahagún, Archbishop of Toledo, Grand Driver of the Facundino Monastery, Co-Founder of the Town] (hermitage in background).

Bernardo de Sedirac (aka Bernardo de Agen, Bernardo de Aquitaine, Bernardo de Cluny, or Bernardo de Toledo, was born ca. 1050 in Agen [in the department of Aquitaine in southwestern France] and died in Toledo 1128. He belonged to the ancient family of the viscounts of Sédirac, whose castle is near Agen. An illness forced him to give up a military career and instead enter the monastic life. He became a monk of the Abbey of Cluny and was sent to Spain to assist in the reforms of Pope Gregory VII, especially the substitution of the Roman liturgy for the Mozarabic. He was appointed Abbot of the Monastery of San Facundo at Sahagún in 1081. After the conquest of Toledo in 1085, he was appointed Archbishop of Toledo in 1088 by Alfonso VI of Castile, a great patron of Cluny.

His statue holds in one hand a sheaf of wheat and in the other the Book of Hours with the motto “Ora et Labora” (pray and work), of the Benedictine Order.

11:06 AM – Virgen del Puente: Right side of gate: statue of Alfonso VI with sign “Sahagún Centro Historico de la Orden de Cluny” [Sahagún Historical Center of the Order of Cluny].

11:06 AM – Virgen del Puente: statue of Alfonso VI on right side of gate.

11:06 AM – Virgen del Puente: statue on right side of gate with sign: “Alfonso VI El Bravo 10[65?]-1109 Rey de León, Castilla y Galicia, Fundador de la Villa de Sahagún, Protector del Camino y de la Orden de Cluny” [Alfonso VI the Brave 10[65?]-1109 King of León, Castile and Galicia, Founder of the City of Sahagún, Protector of the Camino and of the Order of Cluny] (hermitage in background).

Alfonso VI was born before June 1040 and died in 1109; he was King of León from 1065, King of Castile and de facto King of Galicia from 1072. He was the middle of three sons of King Fernando I of Castilla y León. When his father died in 1065, the kingdom was divided. Alfonso was allotted León, while Castile was given to his elder brother Sancho, and Galicia to his younger brother Garcia. Alfonso was the first to violate this division. In 1068, he attacked Galician territory. In response, Sancho attached and defeated Alfonso. However, three years later, in 1071, they joined forces against Garcia. Sancho marched across Alfonso’s León to conquer the northern part of Galicia, while Alfonso took the southern part. Then, in 1072, the two older brothers turned on each other. Sancho was victorious, but was then assassinated, opening the way for Alfonso to claim Sancho’s crown and reunite the territories of their father.

He protected and energized the Camino de Santiago. His statue, in warrior dress, looks toward Sahagún.

We arrived at Calzadilla de los Hermanillos (pop 200) around noon.

Calzadilla de los Hermanillos [Little Road of the Little Brothers] is still in the Tierra de Campos region. The village of Calzadilla was founded back in 1100, but its origins date back to Roman times. The Calzadilla part of the name refers to its location on the Roman road Via Trajana. The Hermanillos part refers to Benedictine friars (little brothers) who came here from the nearby Monastery of Sahagún during the 10th and 11th centuries.

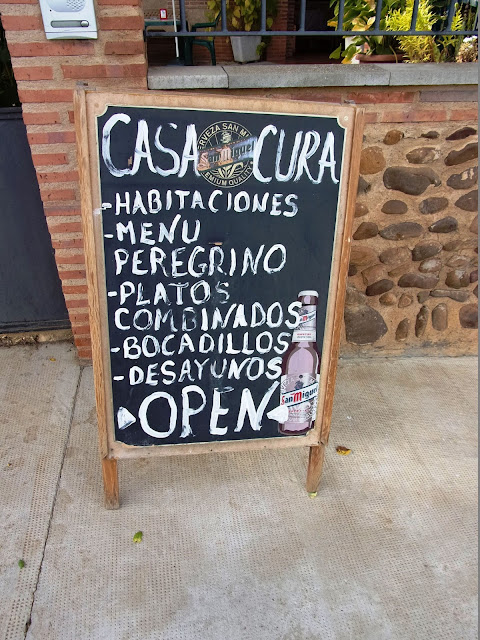

At Casa El Cura (now a Hotel) we got a double room with bath for 45€ (no meals included) and paid 5€ for them to do our laundry (rules posted in the room said no washing clothes in the room and hanging them in the window). We got sellos.

6:17 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: Casa El Cura exterior.

In 2007, María Emilia Santamarta bought a property (Grundstuck) from the local priest and built this small hotel named Casa El Cura [house of the curate] because her daughter needed a job and an increasing number of pilgrims needed a lodging other than the albergue, which was always booked up. In January 2008, she was featured in an article in Der Spiegel, because of the popularity with German pilgrims. The daughter Gemma and her husband Lionel run the hotel, but the mother is also involved.

We ate lunch there: MT got sopa de verduras (puréed vegetable soup) (5.50€); Don passed, but Lionel suggested white rice with lemon and white asparagus for the stomach (gratis); flan (3€). Lionel also gave us some tablets to dissolve in water for electrolytes. Then we rested for a while (all afternoon).

12:11 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: Casa El Cura - Gemma and MT with old photo in dining room.

12:11 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: Casa El Cura - Gemma and Lionel with old photo in dining room.

6:19 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: Casa El Cura - old photo in dining room.

Sunday, September 07, 2014, 8:39 AM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: Casa El Cura - dining room and staircase to habitaciones (rooms); our room was just to right at top of stairs.

8:32 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: Casa El Cura - dining room from balcony next to our room (MT at table on left); window at top left had stained glass.

8:32 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: Casa El Cura – stained glass window on balcony across from our room (telephoto, 186 mm).

1:58 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: Casa El Cura - our room.

1:58 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: Casa El Cura - our room.

Then we went to the one small tienda (grocery store) in town (the sign now said “Tienda Shop Supermarket”) for fruit and yogurts. It was run by a very friendly little man.

5:42 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: tienda – owner and MT (wide angle showing most of his store).

5:43 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: tienda – owner and MT (close-up).

5:43 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: tienda – owner and Don.

5:45 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: tienda owner outside his shop with sign “Tienda Shop Supermarket.”

We walked to the Iglesia de San Bartolomeo (no mass).

Probably before the arrival of the Benedictine friars (little brothers) from the nearby Monastery of Sahagún, there was in Calzadilla a Visigoth or Mozarabic church that was destroyed by the Arab chief Almanzor in the course of his persecution of the Christians of León and Galicia. On the pile of rubble, the church of Calzadilla was rebuilt and dedicated to St. Bartholomew. This church, renovated during the 16th and 17th centuries, is the one that survives.

6:05 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: view down street to back side of Iglesia de San Bartolomeo; elderly ladies on bench.

5:48 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: MT and Iglesia de San Bartolomeo.

In the church square, we looked at the very informative display of the intricacies of Roman road construction in the Centro de Interpretación de las Calzadas Romanas Calzadilla de los Hermanillos.

The Centro de Interpretación de las Calzadas Romanas Calzadilla de los Hermanillos opened in 2012, financed by the Province of León. The display includes a stretch of the Via Trajana, 38 m long and 5 m wide, preserved and cleaned by the city of Burgo el Ranero as part of the project, which also includes another stretch of 25 m cut with cross sections to show the various layers of fill. The center also has a 6-meter long stone canal, remnants of a Roman mill, and a Roman milestone.

5:50 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: section of reconstructed Roman road.

6:20 PM [taken at 550 PM] – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: MT on reconstructed Roman road (similar to what we actually walked on some days).

5:53 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: sign for “La Calzada Romana” [The Roman Road]; Spanish text [translated] reads:

The Roman road was the model of road used by Rome for the structuring of its Empire. The road network was used by the army in the conquest of territories and, thanks to it, large forces could be mobilized with a speed never seen before then.

In the economic aspect, it played a vital role, since the transport of goods was sped up considerably. The roadways also had a great influence on the diffusion of the new culture and extending Romanization throughout the Empire. The Itinerary of Antonino, from the 3rd century, is the written source that gives the most information on the Roman road network.

The roads joined the cities of all corners of Italy, and later of the Empire, with the political or economic decision-making centers. Travel was easy and quick for the time, thanks to an organization that favored a relative comfort for its users. Designed, first, for military use, it would be the source of the economic expansion of the Empire, and after its end, facilitated the great invasions in the barbarian peoples.

5:52 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: sign for “La Construcción de las Vías Romanas” [The Construction of Roman Roads]; Spanish text [translated] reads:

When the decision to build a road was made, the delimitation of the route was entrusted to surveyors, Roman mensores.

In general, Roman roads are very rectilinear on flat land, avoiding flooded areas and the vicinity of the rivers. The roads were widened in the curves to allow carts to turn better.

Construction was entrusted to, among others, construction companies whose contracts were granted by authorized officials. Sometimes the legions collaborated, when the civil administrative structure was not yet imposed in that territory.

The process of construction of a road had several distinct phases, which provided these roads extreme durability that, in some cases, has allowed them to survive up to our days.

- Deforestation. It began by deforestation or clearing of the longitudinal trace.

- Grading. Prior to the construction, the roadbed was leveled, with the relevant works of grading, rock dumps, and filling.

- Delimitation of the roadbed. The width of the carriageway was then defined between two parallel curbs.

- Foundation. In the space between the curbs rough stone is placed, creating a layer of solid and durable foundation.

- Intermediate layers. On this foundation was placed a filling of sand or gravel, in one or more layers of different sizes, decreasing the size of the material as it ascends to the most superficial layer. Then each one of them was tamped.

- Surface layer. Finally, the road surface was covered, preferably with compacted pebbles mixed with sand.

5:48 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: Roman Road display sign: “Centro de Interpretación de las Calzadas Romanas Calzadilla de los Hermanillos” [Center for Interpretation of the Roman Roads Calzadilla de los Hermanillos]. Spanish text [translated] reads:

The Roman road between Sahagún and León is part of two of the routes mentioned in the Itinerary of Antonio (3rd century): Italy to Hispania and Aquitaine to Astorga. These two corridors thus connected Virivesca (Briviesca) and Lancia (Villasabariego). In Briviesca it forked, on the one hand, towards Pamplona and Aquitaine and, on the other hand, toward Sasamón, Zaragoza and Tarragona. From Lancia it also headed towards different directions, on the one hand to Legio VII Gemina (León) and, on the other, towards Asturica Augusta (Astorga).

Throughout this route, in the province of León, the route is formed by a packet of gravel or sand (graded aggregates) of practically homogeneous coarse sizes, about sixty centimeters in thickness and a width of about six meters. Sometimes there are some curbs fitted to a layer of foundation, formed from thicker sizes, up to 15 centimeters in diameter.

The time of construction is not known, but it is easy to assume that the segment Segisamonte (Sasamón) - Asturica (Astorga) was built by Augustus in the final moments of the Cantabrian Wars, about the year 19 BC. At that time, in which the territory was pacified, the Roman road was built to connect the newly established towns, León and Astorga, with the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. In this sense, its construction would probably be contemporary to the road from Astorga to Bracara Augusta (Braga) by way of Petavonium (Rosinos de Vidriagles) and Astorga to Lucus Augusti (Lugo). Its purposes are therefore more commercial that military, since the roads were not built until the territory was Romanized. This route, like all of them, was cared for by various stages or mutatio (postal stops) and the same mansio or stopping places in the cities. This corridor was one of the most important for the evacuation of the gold extracted from the peninsular Northwest, whose neurological center was Astorga.

Around the year 813, at the time of King Alfonso II the Chaste of Asturias, a Christian hermit called Paio told Bishop Teodomiro Gallego, of Iria Flavia, that he had seen some lights hovering around on an uninhabited mount. Finally, in this environment, they found a tomb where there was a body of St. James the Apostle, with his throat slit and with his head under his arm.

The legend was born, and from that moment, Compostela became the third most important nucleus of medieval pilgrimage, after Rome and Jerusalem. On their way to the tomb, thousands of faithful from all over Europe began to use the old Roman road as the way of pilgrimage.

Past and present take the same course in Calzadilla de los Hermanillos, making this town today one of the more prominent within the route.

5:49 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: sign about “Construcción, Dimensiones y Composición de la Calzada” [Construction, Dimensions, and Composition of the Road]; Spanish text [translated] reads:

The construction of the Roman road began by draining the land, that is to say digging a ditch, then incorporating stones of different sizes to fill the area, using materials extracted from the vicinity of the work.

To build a solid road, the larger stones were placed in the base, and on top of these was established a layer of smaller stone touched up with sand or gravel. The work culminated with a surface layer, which was sand (graded aggregates) or gravel mixed with small stone and well compacted. In exceptional cases (usually inside or in proximity to cities) roadways were paved or covered with stone slabs (flagstones).

The final profile of the road is similar to a trapezoid, with quite sloping lines, which permits the easy flow of rainwater to the ditches or outside the embankment. The road was usually bounded on the sides by ditches (gutters).

The total height of the successive layers was from 2 to 4 Roman feet, varying the width of the tread area between 4.5 and 9 meters depending on the importance of the route and/or the orographical [physical geography pertaining to mountains] characteristics of the environment.

According to Vitruvius, a Roman military engineer, an ideal road had to consist of four layers: statum, rudus, nucleus and pavimentum, although in this field, as in others, the genius of the Romans was their ability to adapt to their needs and the resources of each region.

5:49 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: section of reconstructed Roman road showing different layers.

5:51 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: sign for “El Miliario” [The Milestone]; Spanish text [translated] reads:

A miliario or milestone (from Latin miliarium) is a cylindrical, oval or parallel-piped column that stood at the edge of the Roman roads to indicate distances every Roman mile, equivalent to a distance of approximately 1,481 meters.

It was usually of granite, with a cubic or square base and measured between 2 and 4 meters high, with a diameter from 50 to 80 centimeters.

The first known milestones date back to the final period of the Roman Republic, but the vast majority of those preserved were created under the High Empire and, to a lesser extent, in the 3rd and 4th centuries.

Most of the milestones bore engraved inscriptions recorded directly, depending on the importance the road or the closeness or remoteness from Rome, or the cities of origin and destination. The inscription always consisted of a series of well-defined parts:

1st) The full title of the Emperor under whose mandate the road was built or modified.

2nd) The distance from Rome or the most important town of the road.

3rd) The governor or the military unit responsible of the work on the road.

4th) The expression refecit or reparavit if it was a work of road maintenance.

In the 4th century, the milestones lost their indicative functionality, becoming an element of political propaganda of the emperors.

5:51 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: milestone (reconstructed) with inscription “Ab Astvrica – MP LIII” [From Astorga – MP 53].

6:23 PM [taken at 551 PM] – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: Don by milestone (reconstructed) with inscription “Ab Astvrica – MP LIII” [From Astorga – MP 53].

5:51 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: sign for “El Transporte del Agua en el Imperio Romano” [The Transport of Water in the Roman Empire]; Spanish text [translated] reads:

The engineers were true masters in the construction of the water supply networks, and during their Empire, knew how to wisely take advantage of all the water resources: underground reservoirs, rivers, runoff water…

The best example of these infrastructures for the supply are the aqueducts, which were built with the intention of overcoming the geographical features that existed between the springs or rivers and the cities.

But the transport and subsequent supply of water also included other elements: large pipes, wells, dams, canals…

When planning the supply of water for a population center, the Romans first sought a source of water. This was channeled by the construction of a canal, allowing the slope of the terrain to carry the liquid element to an artificial lake or a dam. This ensured the constant supply of water throughout the year.

From this point, water could be transported by canals and channels, whether stone, ceramic pipe or lead. In this way, water from the artificial lake reached the towns.

Photo of “Canaleta en Calzadilla de los Hermanillos” [Small Canal (Channel) in Calzadilla de los Hermanillos].

5:52 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: stone “canaleta” (channel) in display.

5:58 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: view to W down street, on way back to Casa El Cura.

6:06 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: mud brick building.

On the way back to Casa El Cura, we passed the Ermita Virgen de los Dolores.

The Ermita Virgen de los Dolores (Chapel of Our Lady of Sorrows) was erected by friars from Sahagún. The hermitage preserves certain structures similar to the Romanesque brickwork of Sahagún. It was restored in the 16th century along with “la panera” (the breadbox), a building close to the church that, in its time, served as a corn exchange or bank of loan of grain,

6:13 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: Ermita de la Virgen de los Dolores – side view.

6:14 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: sign for “Ermita de la Virgen de los Dolores”; text [translated] reads:

During the 10th and 11th centuries, the frailecillos [little friars] who came from Sahagún erected a chapel dedicated to the Virgin of the Sorrows, patron saint of Calzadilla de los Hermanillos, and that has always inspired great devotion among its inhabitants.

The hermitage, whose condition is very good, displays the classic attributes of the Romanesque-Mudéjar focus typical of Sahagún.

This was restored in the 16th century on the basis of lienzos [literally linens/canvases (walls?)] of mud brick and verdugos [literally shoots, suckers (frames?)] of compacted brick.

The hermitage possesses a single nave. The apse protrudes slightly over the rest of the building, and inside, in the presbytery, one can admire a Baroque altarpiece presided over by the titular image (15th- to 16th-century) in the typical composition of the theme of the Pietà or Sexta Angustia.

The Sexta Angustia (sixth sorrow of Mary’s traditional seven) is receiving the dead body of Jesus from the cross into her arms.

Every year, the image of the Virgen de los Dolores plays the role of one of the most deeply-rooted religious representations among the people of Calzadilla.

On the Friday of Sorrow (Friday before Good Friday), the women of the village process to their benefactress through the main streets of the town, to whom they also dedicate a colorful bouquet of threads, sweets and floral decorations.

The Catholic Church observes two feasts in honor of the Seven Sorrows of Mary; one on the Friday before Good Friday and the other on September 15.

The Leonese traditional banner presides over the ceremony. After this penitential exit, and once the image returns to the temple, men and women sing the emotional salve, a moment of fervor that breaks the silence that accompanies the act.

6:14 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: Ermita de la Virgen de los Dolores – photos of hermitage, statue of Virgen de los Dolores, and nave toward altar with statue of Virgin (Cropped from sign).

6:15 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: Ermita de la Virgen de los Dolores – front view.

6:12 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: sign pointing the way to Casa El Cura.

6:17 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: sign in front of Casa El Cura.

Back at Casa El Cura, MT ate dinner menu peregrino (12€): 1st course: a gazpacho-like soup with ham and hard-boiled eggs; 2nd course: merluza; dessert: lemon mousse; wine; bread; coffee. Don only had the soup (bill lists “salmorejo” [a purée of tomato and bread with oil, garlic and vinegar, served cold; it is more pink-orange in appearance than gazpacho and is much thicker and creamier in texture, because it includes more bread] gratis) and unfusión of manzanilla (camomile) tea (1.50€).

7:14 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: daughter of Lionel and Gemma on tricycle.

7:15 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: Lionel, his mother-in-law (the owner), and her granddaughter.

8:03 PM – Calzadilla de los Hermanillos: Gemma serving wine (with “Casa El Cura” label) at dinner.

Gemma told us that about 100 people live in the town, and 80 % of them are over 80.

No comments:

Post a Comment